By Spencer Logan

March has been an exceptional month in Colorado the last couple years. In March 2019, there was an incredibly widespread and destructive avalanche cycle. Avalanches ran larger than they have in 100 or more years. In March 2020, there was a widespread global pandemic. A virus had a larger global impact than any have in 100 or more years. That had little impact on avalanches, but did have a huge impact on Colorado communities and outdoor recreation. The human impacts of the pandemic arrived as avalanche conditions changed, and the confluence led to an interesting series of avalanche involvements and discussions about backcountry travel and rescuer’s risk.

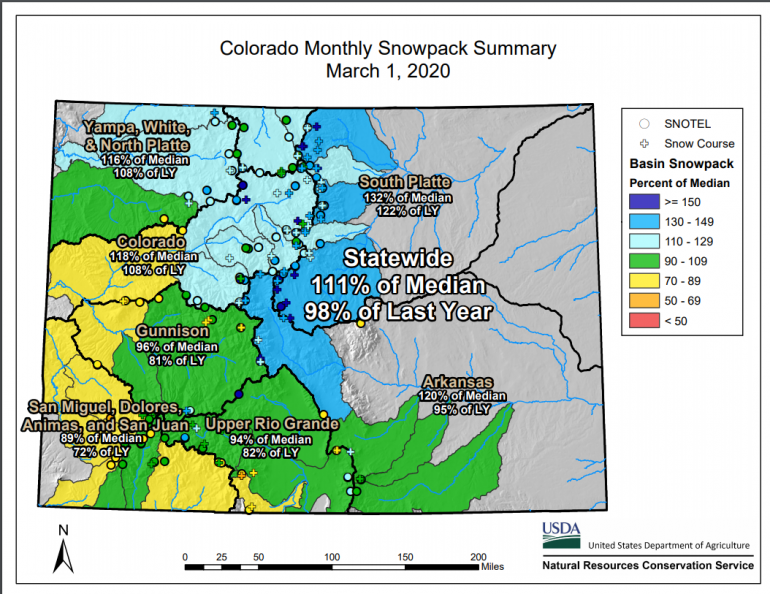

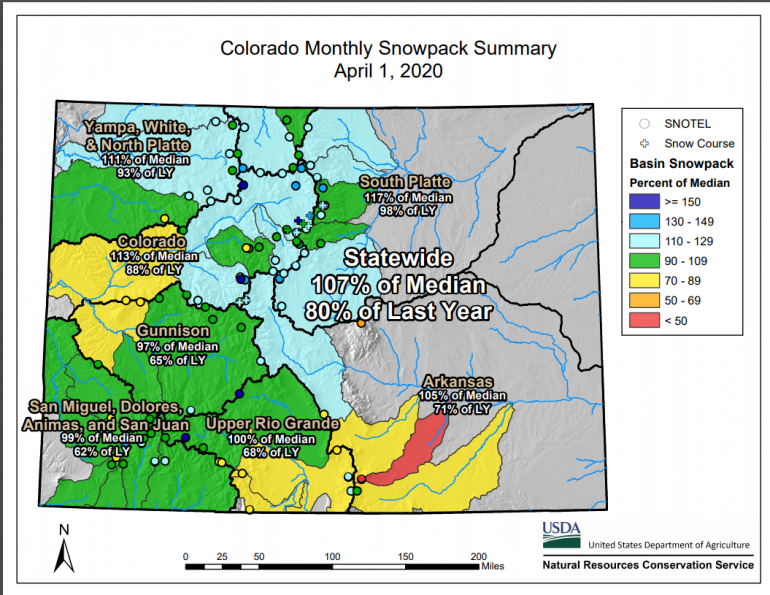

March began with a large north to south difference in Snow Water Equivalent (SWE). Many SNOTEL sites in the Northern Mountains began the month with 150 to 200% of median (1981-2010) SWE. The Central Mountains started near or above the median, while most sites in the Southern Mountains were near or below median SWE. Snowfall through March favored the Southern Mountains, and reduced these disparities. All mountain regions were near or above median SWE by the end of month.

Basin-wide percent of normal (percent of median from 1981 to 2010) snow water equivalent (SWE) across Colorado at the beginning of March and April, and comparisons to 2019 (noted as LY).

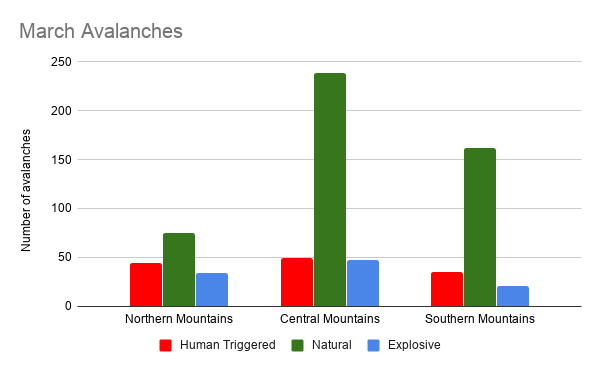

The CAIC recorded 716 avalanches in March. Thirty percent of these avalanches occurred in the Gunnison Zone, and 20% in the North San Juan Zone. Two hundred and forty, or 33% of the avalanches, were human-triggered.

March avalanches by region. Human-triggered avalanches were triggered by backcountry recreationists. Explosive-triggered avalanches were triggered as part of avalanche mitigation efforts. This graph does not include all avalanches triggered as part of hazard mitigation.

The CAIC documented 25 people caught in 23 separate avalanches throughout the month. Seventeen of the incidents occurred in the North San Juan zone, and thirteen of the 17 occurred in the second half of the month. Two backcountry riders were seriously injured, requiring Search and Rescue assistance against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic. Despite the large number of involvements, only those two riders were seriously injured and there were no fatal avalanche accidents.

Across the Northern Mountains,the first half of March could be characterized as warm and dry. Daytime temperatures climbed above freezing almost every day. There were a few dashes of snow, but it was not until March 20 that winter returned. Calendar spring started with a good strom, bringing a foot or more of snow and an inch or two of SWE. Winds were strong and gusty during and after the storm.

Persistent weak layers remained an issue throughout the month. Slabs stacked on top of layers of near surface facets, facet-crust combinations, and basal depth hoar. Following any of the snowfall events, winds drifted snow into touchy slabs. By the end of March, low elevations and sunny slopes began the transition to a warm surface snow. Wet loose avalanches became increasingly frequent.

On March 25, two backcountry snowboarders triggered a small avalanche in wind-loaded snow on a west facing slope above the Eisenhower Johnson Memorial Tunnels. As the avalanche ran downhill, it broke into deeper weak layers and eventually to the ground. This left debris piles 20 feet deep over the Tunnel access roads.

The triggered avalanche covered the Eisenhower Johnson Memorial Tunnel access road in 20 feet of debris.

The Central Mountains fell in the middle of the statewide north-south gradient, and also had a west to east gradient in snowfall and avalanche activity. In the east and west, the Sawatch and Grand Mesa zones, respectively, had a relatively dry month with little avalanche activity. By the middle of the month, low elevations and sunny slopes were well on the way through the transition to a spring snowpack.

After a storm in the first week of the month, warm and dry weather dominated through March 20 in the Gunnison and Aspen zones. Small wet loose avalanches were common. Melt-freeze crusts formed on many slopes, sandwiching several thin layers of faceted snow. Snowfall began on March 20, and quickly produced a cycle of large avalanches followed by another storm and avalanche cycle to close out the month. Despite the number of avalanches recorded, there were no close calls with backcountry travelers reported. Low elevation, wet-loose avalanches did run onto county roads with minor impacts in the Aspen area.

Large natural avalanches on Whetstone Mountain in the Gunnison Zone, March 26.

In the San Juan Mountains, small storms at the beginning of March buried weak snow that developed in February. An emerging Persistent Slab avalanche problem began to take shape but overall the slab was shallow and not heavy enough to overload weak layers. Yet.

As early as March 2 the CAIC documented a skier-triggered slide in Bear Creek near Telluride that failed on the February near-surface facets. With each storm, the slab got slightly bigger and avalanches began to increase from D1’s to D2’s. On March 9, an experienced avalanche worker triggered an avalanche near Wolf Creek Pass, was caught, and buried to his waist. By March 13 the slab was big enough to push many northwest through northeast-facing slopes close to the tipping point and riders began triggering slides at all elevations large enough to bury, injure or kill.

On March 9, this avalanche partially buried an experienced avalanche worker near Wolf Creek Pass.

On March 19 snowfall began, and several feet of snow would accumulate over the next several days. Moderate southwest wind accompanied the storms. Stability slowly decreased as the snow fell, and there were both natural and human triggered slides on deeper weak layers.This increase in avalanche danger coincided with the sugre of backcountry use after ski areas were closed to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. Many riders were caught off guard by this rising avalanche hazard after a relatively stable mid-winter period. Over half of the 146 avalanches reported occurred in the 11 day period of March 13 to 24.

Backcountry tourers triggered, but were not caught, in this avalanche near Ophir on March 15. This was an indication of avalanches to come.

Wind followed the snowfall and triggered a natural avalanche cycle with some of the largest avalanches of the season (2.5 and 3 on the Destructive Scale on March 26). On March 20, there were three close calls in Ophir. In one of the avalanches, both members of the party were partly buried; one of them with only one arm free allowing her to dig out her face and clear her airway. On March 24 a rider was seriously injured after an avalanche slammed him into a tree. A very speedy response by other backcountry groups, Ophir residents, and Search and Rescue saved his life. On March 31, a backcountry tourer was ascending when he triggered an avalanche. He, too, was slammed into a tree and seriously injured. Search and Rescue evacuated the tourer.

While not the only rescues that Search and Rescue groups responded to, the avalanche incidents received lots of attention from the news media. The rescues highlighted the need for SAR volunteers to take additional precautions to minimize coronavirus exposure. The incidents also highlighted the increased need for backcountry travelers to consider their potential impacts on others. The CAIC focuses on avalanches, and encourages backcountry tourers to consider the consequences of an avalanche. But with increased backcountry use and a rapidly changing societal response to the coronavirus, avalanches were just a portion of a larger discussion of risk and exposure.